Valley fever risks can be better managed by understanding soils and desert surfaces

What grows in arid, sandy soils? How do these soils become dust?

Many small organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, grow among the sand and silt particles in dry valley and desert soils. At the soil’s surface, these organisms often form biological webs (“microbiotic crusts”) that keep small sand and silt particles from blowing away.1 In other places, desert soil surfaces are held together by small, closely packed rocks (“desert pavement”) or by salt crusts. These soil surfaces are resistant to strong winds, droughts, and temperature extremes, but vulnerable to mechanical disturbance from human footprints, cars, or grazing cattle. When these soil surfaces are destroyed, they erode more easily and are more likely to release dust into the air.2,3,4,5 This dust is composed of small particles of sand, minerals, and pieces of the organisms that were growing in the soil. While most organisms growing in desert soils are not harmful, spores from the Coccidioides fungus, when inhaled, can cause an infection called valley fever (Coccidioidomycosis). Understanding the conditions that enable the fungus to grow and tracking the processes that release it into dust can help with managing valley fever risks to people and communities.

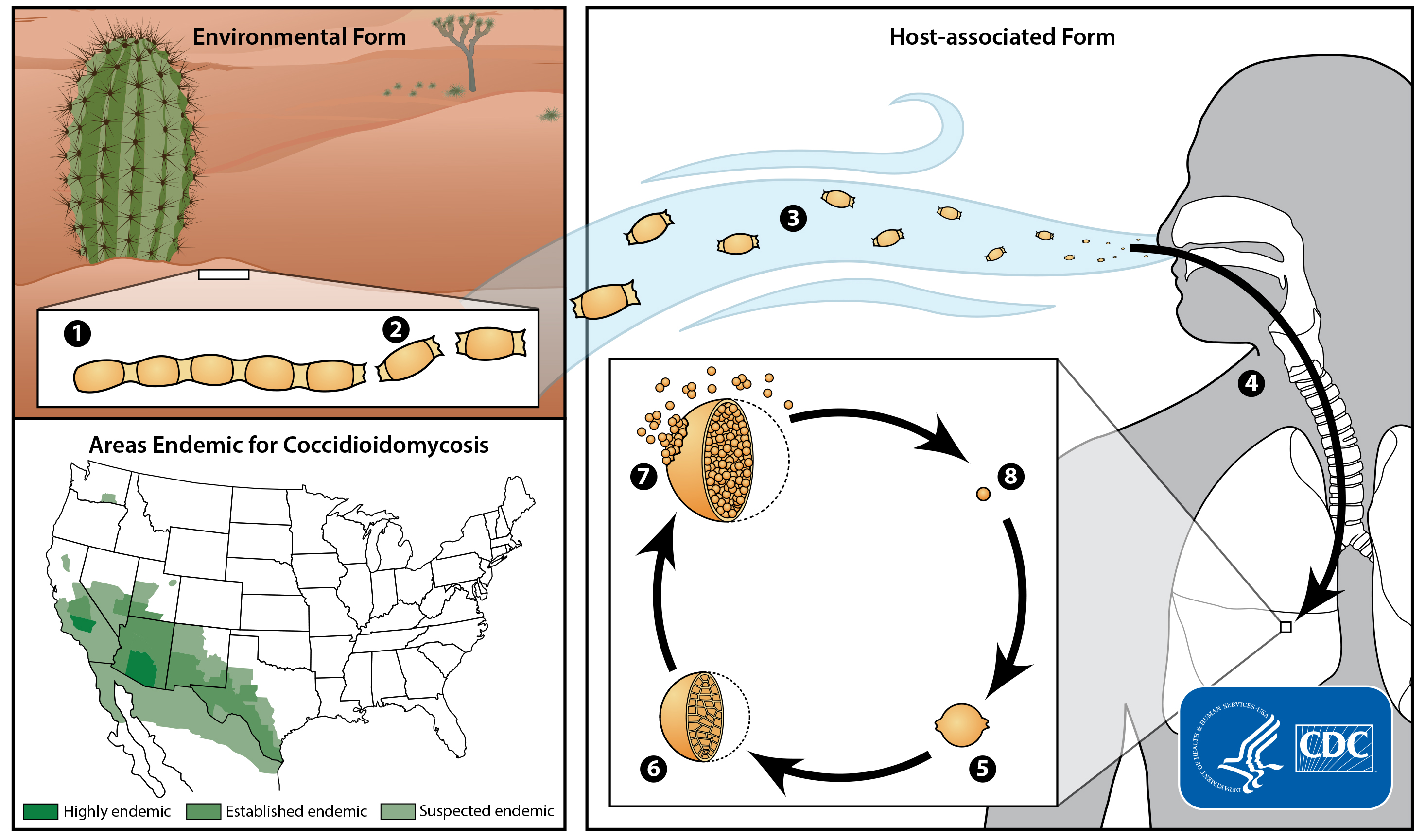

Coccidioides is found in desert soils throughout the southwestern United States, as well as parts of eastern Washington (Figure 1).6 The specific locations where Coccidioides is actively present range in size from roughly 200 square feet to more than a square mile.7 The geological and environmental factors that are thought to determine whether Coccidioides can grow are:8

- Soil composition. Coccidioides thrives in well-drained, salt-rich desert and valley soils made of very fine sand and silt particles.7 Scientists are currently studying whether it can grow in desert soils covered with microbiotic crusts, or if it only grows in disturbed soils, information that will help improve land management decisions in the future.

- Temperature and moisture. Climatically, Coccidioides prefers arid regions with hot and dry summers, cold winters, and little rainfall.

- Distinct wet-dry seasons. Coccidioides seems to be more abundant in areas with distinct wet and dry periods. Seasonally, Coccidioides outbreaks often occur during the dry seasons that follow particularly wet periods.9

- Presence of rodents. Rodent burrows are one risk factor that suggests Coccidioides may be present in a specific location.7

- Agriculture. Coccidioides typically does not grow in tilled and irrigated farmland.7

In soils, Coccidioides grows as a chain-like mold (1). When disturbed, the mold chains fragment into smaller spores (2) that may be inhaled. In the lungs of an infected person, the fungus grows and spreads (5 to 8) but is not contagious. Image Credit: CDC

What can be done to avoid generating dust?

The best way to prevent dust is to minimize the destruction of soils in deserts and semi-arid regions, especially in open areas that depend on microbiotic crusts or desert pavement for stability.1 This can be achieved by:

- Location. Roads and other infrastructure can be built in less sensitive areas, with carefully designed runoff drainage to prevent erosion. Other effective measures include limiting recreational use to specific, concentrated-use areas like well-marked campsites and hiking trails, and avoiding the disruption of desert surfaces in steeper areas, which are more prone to erosion.1

- Timing of disruptive activity. Desert surfaces, especially microbiotic crusts, are less vulnerable during the winter or fall, especially when the ground is frozen. Microbiotic crusts are especially vulnerable during the dry season.

The environmental and geological conditions at a given location can be determined using freely available maps and online resources, like soil maps from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and climate databases from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Together, these tools can be used to help assess Coccidioides risk in any given location. In areas that are likely to be Coccidioides positive, the safest option is to avoid any non-essential activity that may disturb the soils, and when this is not possible, to closely follow the safety precautions recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To minimize health impacts, including the risk of valley fever, many communities require dust management plans for large-scale disturbances of desert and dry valley soils.

How can geoscience be used to help prevent exposure to the valley fever fungus?

The geosciences can help manage valley fever risks by:

- Helping land managers, industrial planners, and the outdoors community identify locations that, based on their geological and environmental characteristics, are likely to have the Coccidioides fungus present in the soil.

- Helping design essential infrastructure in areas likely to have Coccidioides present so as to minimize soil surface damage and erosion.

- Using atmospheric modeling to understand how soil disturbance and dust formation in one location will disperse and affect downwind communities or recreational areas.

More Resources

For more on valley fever as an occupational hazard: Jacobs J A and Grant Ludwig L (2016) - Exposure to Valley Fever in California - Recent Trends and Prevention for Geologists, Construction Workers, and Related Occupations. In: Anderson R and Ferriz H (eds.) - Applied Geology in California

Biological Soil Crusts: Webs of Life in the Desert, U.S. Geological Survey

Don’t Bust the Biological Soil Crust: Preserving and Restoring an Important Desert Resource, U.S. Forest Service

Biological Soil Crusts: Ecology and Management, U.S. Bureau of Land Management

Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Valley Fever and the Expanding Geographic Range of Coccidioides, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever), California Department of Public Health

Operational Guidelines for Geological Fieldwork in Areas Endemic for Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever), U.S. Geological Survey

The Zebra Among the Horses (video about valley fever), New Mexico Department of Health

References

1 Biological Soil Crusts: Ecology and Management, U.S. Bureau of Land Management

2 Sediment losses and gains across a gradient of livestock grazing and plant invasion in a cool, semi-arid grassland, Belnap J et al. (Technical Article)

3 Increasing eolian dust deposition in the western United States linked to human activity, Neff J C et al. (Technical Article)

4 Valley Fever, U.S. Geological Survey (archived website)

5 Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever), National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

6 Valley Fever Awareness, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

7 Exposure to Valley Fever in California - Recent Trends and Prevention for Geologists, Construction Workers, and Related Occupations, Jacobs JA and Grant Ludwig L (Book Chapter)

8 Coccidioides Niches and Habitat Parameters in the Southwestern United States, Fisher et al (Technical Article)

9 Operational Guidelines for Geological Fieldwork in Areas Endemic for Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever), U.S. Geological Survey

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are free to share or distribute this material for non-commercial purposes as long as it retains this licensing information, and attribution is given to the American Geosciences Institute.