EarthComm represents a collaborative effort between scientists, science educators, and others. Try to maintain a collaborative approach in teacher workshops. For example, try to balance the facilitator team by having an Earth scientist work with a science educator, or a teacher work with a teacher educator. Team members should recognize each other's areas of expertise and acknowledge these openly throughout the workshop so that teachers can see deliberate collaboration in action. Many EarthComm teachers will have to depend on such collaboration as they teach the modules, especially when implementing the curriculum for the first time in their classrooms.

In an in-service workshop, you may have only one day to work through a module that consumes nine weeks of the school year. Attention to logistics is essential, and it is strongly recommended that you consider a third leader to provide logistical support needed to make the workshop run smoothly. Much of the logistical work must be done in advance-especially gathering and organizing supplies. It must be clear who will do these steps (see "Logistical Details" below). It is worthwhile to acknowledge that work, even if the person is not in the immediate group.

Of course, the specific make up of the team will depend on local circumstances and resources, but consider the balance of expertise that individuals bring to the workshop. One team included:

- An Earth scientist who was very aware of issues in science education.

- A science educator well-informed about the nature of science and current Earth science research.

- A science education student who was primarily responsible for workshop logistics.

During the workshop, tell participants about the area of expertise each team member brings to the workshop and the interdependencies of the team members. Doing so may help reinforce the benefits of forming collaborative partnerships among people whose expertise complements one another.

The following material outlines strategies for incorporating important elements of interactions into workshops.

Open acknowledgement of expertise and limitations.

Members of the facilitation team can talk openly about the expertise of other team members as well as about their own limitations. For example, a participant might ask a question in a science area that is unfamiliar to the science educator, and he or she might defer that question to the Earth scientist on the team. This might go the other direction if the question pertains to aspects of assessment in science education. As team members openly acknowledge expertise and limitations, they implicitly acknowledge the strength of a collaborative approach, the inevitability of limits to knowledge, and the mutual respect that exists between members of different professional communities.

Strive to openly acknowledge the expertise of the workshop participants. You can do this in several ways:

- Look for opportunities to turn questions over to other participants for ideas. Many of the participants might have ideas about how to overcome certain barriers to reform, for example, such as lack of immediate administrative support. However, the person who was asked the question should answer so that the questioner is not frustrated in her or his attempt to find out what that person thinks.

- Use workshop participants as positive examples whenever possible. These examples may be from observations you have made in your workshop, or they may come from your knowledge of that person's teaching experience.

- Acknowledge your dependence on outside information for the responses to some issues. For example, cite the sources of your ideas when you know them so that it is clear that you are learning from third parties and are not trying to present yourself as omniscient specialists.

Ongoing reappraisal of your approach with input from participants Consistent with learner-centered approaches to teaching, workshop leaders should solicit input from the learners on an ongoing basis. It is not enough to make a general offer that everyone should feel free to share comments. Have a mechanism for that sharing so that participants know when they will be able to have their say.

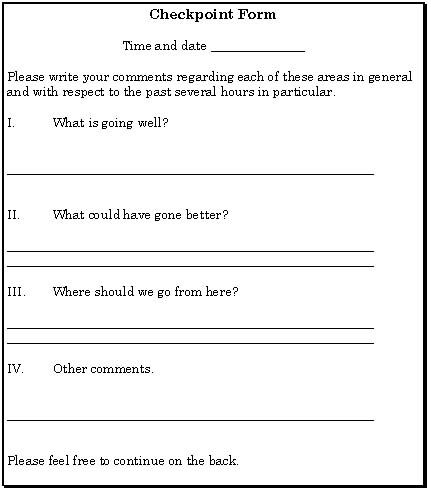

One approach to receiving feedback is the use of periodic "Checkpoints" (see below.)

Checkpoints are a formative assessment technique that is as useful in classrooms as it is in workshops. A checkpoint has three broad questions: What is going well? What could be going better? Where should we go from here? Ask participants to complete a half-page checkpoint form when you break for lunch and as you close for the day. To organize the collection and review process, place a box in some part of the room labeled "checkpoint forms", and consider using different colored sheets each day. The next time the group meets (after lunch or the next morning) share the input by putting representative comments on an overhead. There is no need to provide quantitative data, as one thoughtful person can provide as much insight as a large group. Discuss how you might respond to each of the issues or comments that have been raised. This can be delicate because you do not want to be defensive, nor do you want to make changes that undermine your later plans. Try to shift the emphasis, timing, and/or your specific practice as you can. Participants will often see contradictions in responses to the first two checkpoint questions (such as when someone comments that the pace of a morning is just right, while another says it is too fast, and a third says it is too slow). Participants often spontaneously and openly recognize the difficulty workshop leaders face in making everything suit everyone's needs.

You can also use less formal methods to reappraise your approach. For example, listen for comments that seem to be either particularly emotionally charged or inserted into conversations where they don't seem entirely fitting. The latter comments often include ideas that someone is looking for an opportunity to share.

To deal with emotionally charged comments and insertions, you may find it helpful to use a "back pocket" question; "Could you tell me more about that?" This non-judgmental response allows the speaker to have her or his say. Knowing what to do next, such as opening a discussion about the topic or suggesting that the topic be saved for later, is a judgment call. However, many times the person will be satisfied to have had an opportunity to share the idea, and no further action is necessary. You should however take these comments seriously and discuss with your co-presenter how you might respond.

Workshop leaders should use daily debriefing sessions, held immediately after participants depart, to discuss specific responses to issues that arise. Begin by discussing the afternoon checkpoints. Then, consider your goals, whether or not goals were met, your upcoming goals, and whether or not you need to amend your goals. Review the plan for the next day and consider appropriate alterations. The daily debriefing session is vital to reappraising your approach, so schedule time for it each day.

Speaking Stick

This is a strategy picked up from indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, but put to use in ways that they might not recognize at all.

The strategy involves designating a stick or some other implement as the device by which someone gains the floor, so to speak. You can use sticks, rocks, or an inflatable globe (the latter is safest to throw in a classroom). The person who has the speaking stick may say his or her piece, but tries to limit it to 3-5 sentences at a maximum. Then that person passes the speaking stick to another participant. A participant who would like the stick signifies this by turning a hand over on his or her lap (or the table, depending on how the group is seated) so that the palm is up. Two palms indicate that the person REALLY wants to get the stick. However, the person with the stick may decide he or she would like to hear from an individual who is not indicating a desire to speak. Yet, a person who is handed the stick may also pass it on without comment.

In practice, the speaking stick strategy works to the benefit of those who would not ordinarily jump into a conversation, and helps those who are more likely to speak monitor the frequency of their comments (i.e. their "air time") with respect to the rest of the group.

Demonstrate Respect for The Participants

Your actions and words should demonstrate to each participant that you value his or her ideas in particular and that you are respectful of him or her in general. For example, as participants raise questions, strive to give all participants the opportunity to provide input. They may decline, but asking an otherwise quiet person to make a comment may be enough to get him or her to share insights. Also, if there are a few particularly vocal participants, you may have to intervene so that everyone can be heard in a timely manner. One approach is a "speaking stick" strategy (see below), which places control of the flow of a conversation in the hands of the participants.

Careful time management provides yet another way to demonstrate respect for participants. Let them know that you want to start on time so that those who made sure they were ready will not be disappointed. You may have to put off your responses to individual requests (like those made at the moment the day is to begin for example) in order to maintain the schedule for the group. If you are late or run over the allotted time, you risk sending a message that you do not value participants' time. While it is unwise to chide someone for being late or having to leave early (participants often have conflicts at specific times), it is best to maintain the group's overall schedule to the extent possible.

Delphi Technique

This technique is derived from a book for writers called Writing Down the Bones, called "timed writings." The process requires three steps:

Step 1: Initial timed writing - Participants are all given a sheet of paper so that the pages look alike. They do not write their names on the papers. They are given a sentence stem to complete such as "The thing I think is most important about inquiry-based teaching is..." or "When I think about issues of 'relevance,' what comes to mind is..." The participants are asked to write, non-stop, for thirty seconds. During that writing they do not stop their pen, they do not edit, they do not worry about spelling or grammar, they do not worry about the clarity of their expression. They just write. At the end of thirty seconds, they may choose one idea from what they wrote in the first episode and expand on it for another thirty seconds. The same rules apply as before.

Step 2: Response Writing - You can also time this segment, but make the time interval one minute. In this episode, collect the papers, mix them up, and pass them back out. It works well to collect them from half of the room at a time, shuffling each half, and then passing them back out to the other side of the room. That way nobody should end up with her or his own paper. After taking a few seconds to read what is on the paper, each person gets to write a response. They can comment in any way they wish, but we encourage them to explain themselves. Since participants have a full minute, they can be a little more thoughtful about how they write. After the minute is up, collect and redistribute the papers again, and have participants respond again. It is OK if someone gets her or his original paper back. This can be repeated a third time.

Step 3: Open Sharing -- After the second (or third, if you wish) response, participants choose ideas to share with the group that they think are worth considering. They do not have to agree with the idea, but they should not tell the group whether they agree or not. These ideas are recorded on a board or chart paper. After everyone has had a chance to share one idea, the workshop leader moves into a discussion mode by asking such questions as: Does anyone see any ideas written here that go well together? Or conflict? Which of these might influence us as we work to implement EarthComm?

Many participants will be specialists in particular areas of science (geology, astronomy) or teaching (teaching students with special needs), and can be called upon to share their expertise. All participants have a measure of expertise at their own job and the specific roles that they must fill within their schools and classrooms. For instance, all teachers have some measure of expertise regarding their students (the 160 ninth graders they see each day), and students of the age they teach (the "ninth grade student"). While this expertise may be based primarily on their experience, the value of this experience should not be under-rated. Questions can be turned to the group and to individuals who might have specific and worthwhile input. One technique is called the "Delphi technique," which is often used in collaborative decision-making. This can be coupled with anonymous timed writings as a mechanism for promoting open participant-to-participant idea sharing (see box, below.)

This is a brainstorming approach to discussion. As in any brainstorming session, it is important to accept all ideas, avoid closure, and keep the tone light.

After hearing participants' ideas and concerns, the workshop leader can discuss the issues as they relate to EarthComm and can suggest to the group to watch for how other of the ideas are factors in what is done in the remaining days of the workshop.

Finally, giving participants input into how they spend their own time demonstrates respect for their knowledge of their own needs and interests. This is particularly important when long-term projects are undertaken. For example, in the workshop itinerary that is given below, participants spend time preparing and presenting sets of EarthComm activities. Out of respect for each participant's interest in addressing specific areas, ask participants to tell you what activities they would like to work on. You can use a strategy from marketing research called the "passion points" technique (see box, below).

Passion Points

In a past life, one of the developers of this manual worked in marketing and ran across a technique that works well for giving individuals input into the formation of groups for projects. In longer workshops, of several days at least, it is possible to have teacher participants become familiar with and lead EarthComm activities. After the general work of the groups is discussed, each participant is told the options for group placement. In the case of EarthComm these options relate to which chapters the groups will prepare to present to the other participants.

After the group has gone over the general content outline of EarthComm, which they would have looked over the evening before, the workshop facilitators can ask them to make a list of their first, second, and third choice of what group they'd like to be in. In addition, though, they are told that they each have some number of "passion points" to assign to the choices they make. The number of passion points is usually the number of options times three plus one. So, if there are three options, each participant will have 10 points to assign (3 x 3, +1 = 10). If there were four choices then each person would have 13 points to assign (4 x 3 +1). The participant can assign the points any way he or she chooses, but each choice must get at least one point. So, with three choices, one participant might assign the points as 5 points for the first choice, 3 for the second, and 2 for the third, while a second might assign 8 points for the first choice, and 1 point for each of the other two. That suggests that the second person is somewhat more passionate about getting to work on his or her first choice than is the other. Knowing this helps us to form groups that take individuals' priorities into account.

Avoiding "the Don'ts"

Experienced workshop leaders know that there are several things that are generally not good ideas. Based on their experience, resources, and the input from participants, this is a summary list of "Don'ts":

- Don't go in unprepared-demonstrate respect for the group by planning ahead, and working the plan.

- Don't be too committed to a particular approach or activity-if something isn't working, acknowledge that and shift the plan.

- Don't apologize for what was done it good faith by you or someone else-our ideals sometimes get the best of us, leading us to focus on how the end product does NOT reach them instead of how it does.

- Don't gloss over mistakes, but don't dwell on them either-mistakes are part of any human system, and participants will generally understand.

- Don't get caught up in trying to entertain the group-spontaneous humor is genuinely appreciated, but forced humor can be seen as inappropriate, especially if it offends.

- Don't go over time, especially at the end of the day-stick to the schedule as much as possible, and tell (or, better, ask) the group if an alteration is needed so it does not seem careless.

- Don't treat all participants or groups the same-get to know them and their specific needs as much as possible. Acknowledge differences in background as a strength of the group and encourage participants to help each other.

- Don't make the workshop "about" you-anecdotes are often more fun for the teller than the listener, and as much as possible attention should be turned to the participants, their actions and their attempts to do things.

- Don't forget that everything you do should be geared toward conveying specific messages-know your goals for a day and don't let yourself get distracted, or distract the participants either through digressions or habits such as pacing.

- Don't neglect "off hours" when participants are not from the local area-consider how those individuals might want to spend time. Collect information about local sites and help participants make connections with others with similar interests so that off hours are enjoyable.

Logistical Details

There is an old saying that "the devil is in the details," and that is generally true for any workshop as much as for anything else. Below are some of the issues that you should be sure to check into before the workshop:

- What materials are needed for activities? How will they get to the workshop site?

- If materials are being shipped, is it better to have the materials go to the workshop leader so they can be checked before the workshop? (Such as to the facilitators' hotel.)

- Do some participants have specific dietary, mobility, or other needs? How can these be accommodated?

- Where will participants find parking? Are permits needed?

- Where are some suggested spots to eat evening meals that can be provided to participants from out of town?

- How should out of town participants get breakfast in time to be at the workshop on time?

- What form of transportation can be used from lodging to workshop site?

- What materials can workshop participants keep? What must be returned?

- What AV media will be needed for the workshop? Do presenters know how to use it? Where are extra bulbs and other backups?

- What kinds of activities will be done and what kinds of physical resources (sinks, windows, doors to outside) will be needed for those activities?

- Is the physical space large enough for the number of participants to be as active as is called for?

- Are there special tours and/or other events that are available for participants to take advantage of during their off hours?

- How can participants keep in touch with their homes and workplaces? Where can they find telephones? Where can they access e-mail?

- If participants would like to use computer resources, where are they available (e.g. computer labs)?