Geologic maps are being used in Kentucky to identify areas that have high potential for development of karst features, such as sinkholes and caves.

Defining the Problem

A new interstate highway, I-66, is being planned to pass through the vicinity of Mammoth Cave National Park (Fig. 1). It is one of the nation’s most popular parks and is also extremely vulnerable to environmental impacts. This area is a classic karst terrain characterized by caves and sinkholes. These features form as naturally acidic water moving from the surface landscape through fractures in limestone bedrock slowly dissolves away the rock. Mammoth Cave depends upon groundwater for its natural development and fragile ecology, but runoff water or contaminants can drain directly into karst passageways with little filtration. Karst features can also subside or collapse under roadways. In order to make informed decisions about the location and design of I-66, transportation officials need information about the local rock units, as well as their structure and relationship to surface features and subsurface drainage. A geologic map provides this information.

Figure 1: A National Park Service ranger leads visitors into the mouth of Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky. Credit: National Park Service

The Geologic Map

The geologic map (Fig. 2) shows the important rock units in the I-66 planning area. The map shows that the southern boundary of the Park is on a resistant sandstone plateau underlain by limestone in which the caves are developed.

Figure 2: Simplified geologic map of the I-66 planning area showing principal rock types of the region. Credit: Kentucky Geological Survey

Applying the Geologic Map

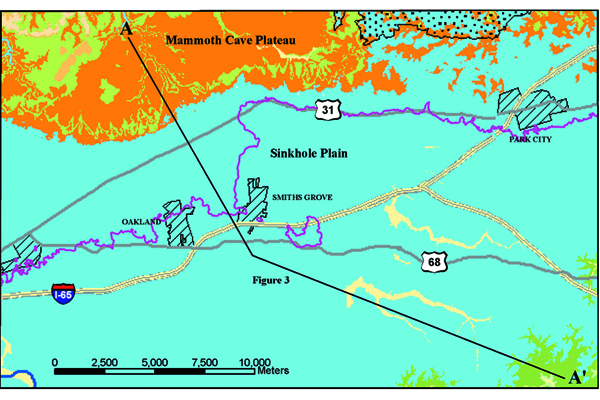

The distribution of surface features, such as sinkholes and streams, is directly related to the rock units shown on geologic maps. Transportation planners can use these maps to identify areas with high karst potential, and thus protect the public and minimize road construction costs by avoiding these regions. Figure 3 shows the distribution of sinkholes and surface streams in relation to the Lost River Chert – an insoluble rock layer within the karst-forming limestones. The presence of the chert layer in the shallow subsurface has resulted in formation of relatively shallow, but broad and complex sinkholes in the overlying limestone north of the chert outcrop. Where the chert layer has been eroded, the underlying limestone contains numerous and deep sinkholes.

Figure 3: Distribution of karst features within the geologic map area relative to the outcrop of Lost River Chert layer. Credit: Kentucky Geological Survey

Conclusion

Understanding karst and conducting karst investigations would not be possible without geologic maps. Karst terranes are present in most of the states in the United States. Geologic maps are being used in Kentucky to identify areas that have high potential for development of karst features, such as sinkholes and caves. Geologic maps are also being used to analyze existing sinkholes to provide an increased understanding of karst development in geologic rock units and to protect areas vulnerable to groundwater pollution.

Additional Information

Case study author: Kentucky Geological Survey

Case study from: Thomas, W.A. 2004. Meeting Challenges with Geologic Maps, p. 30-31. Published by the American Geosciences Institute Environmental Awareness Series. Click here to download the full handbook.