Four examples of managed groundwater replenishment across the state

The Need for Groundwater Management: Sustaining water supplies and preventing hazards

In California, surface water from rainfall, snowmelt, and distant rivers rarely meets the state’s urban and agricultural water needs. Groundwater is an essential water source, providing 35% of the fresh water used in California.1 However, when groundwater is used more rapidly than it is naturally replenished, groundwater management becomes necessary. One of the tools used by groundwater managers is managed aquifer recharge (MAR).

Aquifers, the porous rocks and sediments that hold and transmit groundwater, are naturally replenished by surface water that seeps into the ground. MAR enhances the recharge rate by creating artificial streams and ponds where water trickles into the ground, or by using wells to directly inject water underground. MAR can also be used to improve groundwater quality and prevent some of the negative consequences of groundwater depletion, like ground sinking (subsidence) or the intrusion of salty groundwater from the oceans into coastal freshwater aquifers.2 Because of its arid climate and large population, California is home to some of the oldest and largest MAR projects in the United States. This case study highlights four of these projects, covering almost a century of MAR and water security in California.

Case 1: Santa Clara Valley Water District: Stopping subsidence and storing water

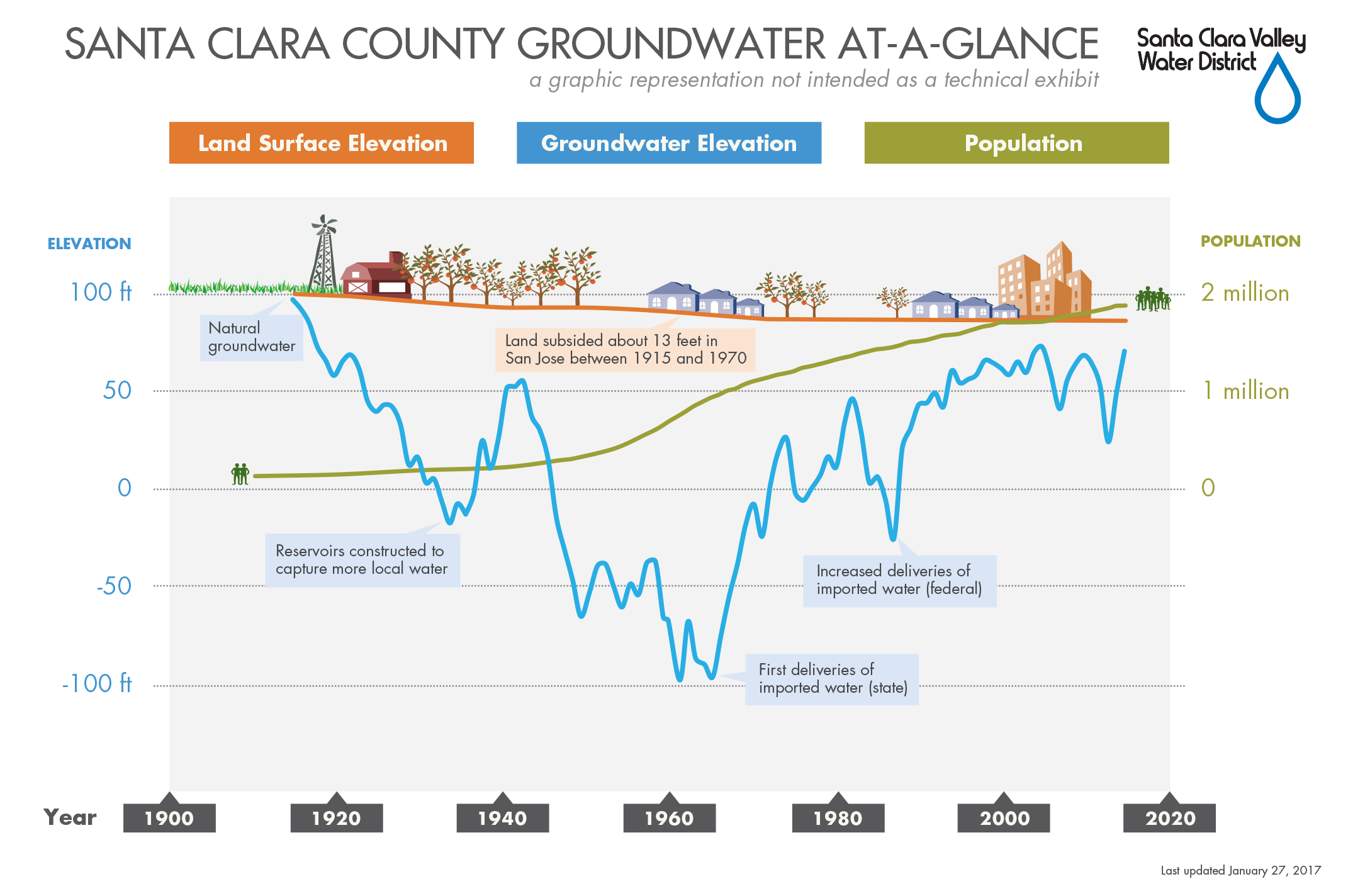

The land in the Santa Clara Valley, better known today as Silicon Valley, began sinking in the early 1900s as excessive groundwater removal caused the ground to compact. The Santa Clara Valley Water District was founded in the 1920s to recharge groundwater supplies and prevent further land subsidence.3 However, local water supplies have always been low, and despite many attempts to optimize the use of local water for aquifer recharge, groundwater depletion and subsidence continued until non-local (“imported”) state and federal waters from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta were made available to the district in 1965 and 1987.3 Since then, groundwater levels have been restored and the subsidence has largely stopped (Figure 1). Today, imported waters still supply two-thirds of the water used for aquifer recharge and half of the total water used in the Santa Clara Valley Water District.4 Of the 2.4 million acre-feet of total groundwater storage capacity, roughly one quarter (double the district’s total reservoir-based surface water storage capacity) is considered safe to use without risking future subsidence.

Santa Clara Valley Water District: Numbers at a Glance5

- Total Aquifer Capacity: 2.4 million acre-feet at capacity

- Target Operational Aquifer Level: 300,000 acre-feet below capacity

- Minimum Operational Aquifer Level: 540,000 acre-feet below capacity

- Managed Recharge: ~100,000 acre-feet per year

- Unmanaged Recharge: ~60,000 acre-feet per year

Land elevation (orange), groundwater level (blue), and population (green) in the Santa Clara Valley Water District since the 1920s. Managed aquifer recharge has helped to restore groundwater levels and prevent further subsidence. Image Credit: SCVWD.

Case 2: Orange County Water District: Preventing saltwater intrusion, improving water quality, and storing water

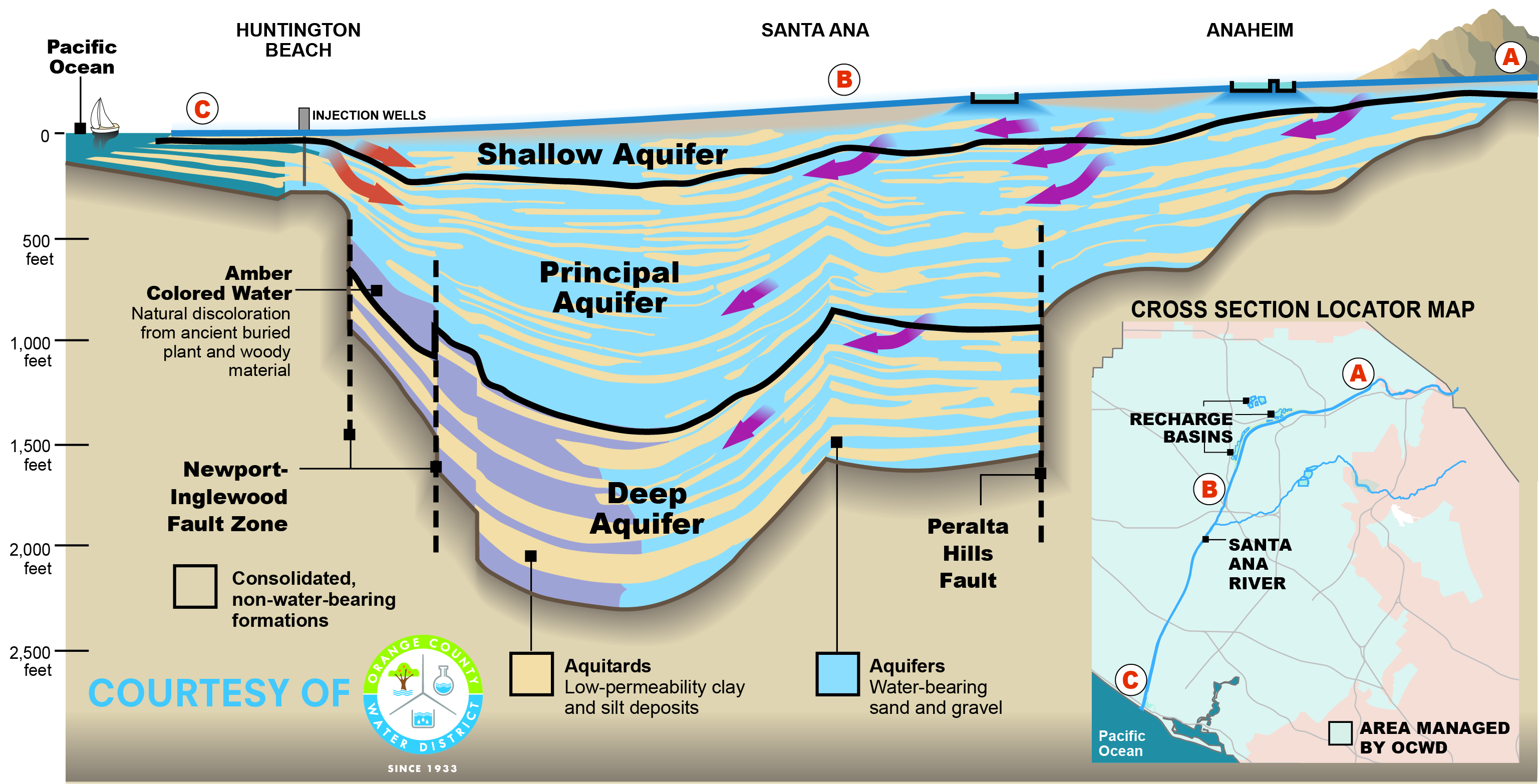

When coastal aquifers are depleted, salty groundwater from the ocean can flow into them. In 1933, this saltwater intrusion threatened the groundwater underlying much of Orange County, and the California State Legislature formed the Orange County Water District.6 Historically, the district has recharged the aquifer with a mixture of excess Santa Ana River water and treated wastewater cleaned to drinking quality standards. In recent years, with the future availability of river water uncertain, the district has invested more heavily in water treatment projects.7 Today, the Orange County Water District manages injection wells by the coast to keep saltwater out, and uses inland spreading grounds (artificial ponds where water can trickle into the ground) to recharge local aquifers (Figure 2). The district closely monitors the amount of water available in its underground reservoirs; monthly data are available in graphical form on their website.

Orange County Water District: Numbers at a Glance8

- Total Aquifer Capacity: 66 million acre-feet at capacity

- Target Operational Aquifer Levels: 150,000-200,000 acre-feet below capacity

- Minimum Operational Aquifer Level: 500,000 acre-feet below capacity

- Managed Recharge: >300,000 acre-feet are recharged and extracted each year

The OCWD uses inland surface MAR techniques and coastal injection wells to recharge groundwater and prevent saltwater intrusion. The quality of the recharged water increases as it flows from inland recharge basins into the aquifer. Image Credit: OCWD

Case 3: Water Replenishment District of Southern California: Stormwater management, water storage, and preventing saltwater intrusion

The Water Replenishment District (WRD) of Southern California was established in 1959 to protect the Central and West Coast Groundwater Basins from saltwater intrusion. Today, the WRD, like the neighboring Orange County Water District, operates inland spreading grounds and coastal injection wells to recharge the aquifers and prevent saltwater intrusion. Half of the water used by the 4 million residents of southern Los Angeles County comes from aquifers managed by the WRD. Historically, the spreading grounds and injection wells used a mixture of local and imported water. More recently, as concerns about the reliability and cost of imported water have grown, the WRD has invested in water recycling and expanded its stormwater capture system to recharge the aquifers with rainwater that would otherwise flow into the ocean. With these investments, the WRD is on track to use 100% local water by 2018.9

Water Replenishment District of Southern California: Numbers at a Glance

- Total Aquifer Capacity: 35 million acre-feet at capacity

- Minimal Operational Aquifer Level: 731,835 acre-feet below capacity10

- Managed Recharge: ~100,000 acre-feet each year11 (in addition to unmanaged recharge)

- Water Extracted: ~220,000 acre-feet each year

Case 4: Kern Water Bank: Stabilizing the water supply for agriculture

The Southern San Joaquin Valley is a major agricultural region. Water needs are high, but the amount of river water flowing into the valley can vary greatly from year to year. The Kern Water Bank was launched in 1978 to stabilize water availability. From a geological standpoint, this region, underlain by a thick, sandy aquifer, is ideally suited for underground water storage. In wet years, some water from the Kern River is used to recharge the underlying aquifers using a series of spreading grounds. In addition, the water bank relies heavily on non-local state and federal waters from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, which are brought in by the California Aqueduct.

In contrast to the three other water districts described above, the Kern Water Bank is privately owned and managed. People or companies own water rights, which entitle them to pump certain amounts of groundwater.

Kern Water Bank: Numbers at a Glance12

- Total Aquifer Capacity: 10 million acre-feet at capacity

- Minimum Operational Aquifer Level: 1.5 million acre-feet below capacity

- Maximum Recharge Rate: ~850,000 acre-feet per year

- Maximum Extraction Rate: ~290,000 acre-feet per year

Recent MAR activities in California: A widely used tool for water management

Under the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, California now requires comprehensive groundwater management throughout the entire state.13 In addition to the four well-established examples described here, there are many new and proposed MAR projects in the state, motivated largely by a need to increase water supply, improve flood protection, and manage stormwater.14 Beyond California, some MAR is now used in dozens of states.

Key Terms, Defined

Acre-foot: An acre-foot of water is approximately 326,000 gallons. This is the average amount of water used each year by a five-person household in the United States, although the amount used varies depending on regional climate and water conservation practices. In California, an acre-foot is the average annual water consumption of two and a half single family households.15

Total Aquifer Capacity: The total aquifer capacity is the amount of groundwater that the aquifer holds when completely full.

Minimum Operational Aquifer Level: This indicates the amount of water that can be safely removed from the aquifer without undesirable consequences such as land subsidence.

Target Operational Aquifer Level: This is the optimal amount of water to have in an aquifer: enough to provide a steady water supply during a prolonged drought, but with enough space to capture stormwater or excess river water in very wet years.

Regulatory Framework and Management Matter

The success of MAR depends not only on having a suitable aquifer, but also on having an appropriate regulatory framework and proper management.

More Resources

For more on these case studies, and MAR in California in general (including technical details): Gamon D A, Zilles J, and Schumann R (2016) - Summary of Managed Aquifer Recharge Concepts and Planning Methods. In: Anderson R and Ferriz H (eds.) - Applied Geology in California

Santa Clara Valley Water District website

Orange County Water District website

Water Replenishment District of Southern California website

Kern Water Bank Authority website

California Academy of Sciences - Recharging Aquifers

International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre - MAR Portal

Netherlands National Committee of the International Association of Hydrogeologists – Management of Aquifer Recharge and Subsurface Storage

Water in the West - Benefits and Economic Costs of Managed Aquifer Recharge in California

AGI Critical Issues Program - Managed Aquifer Recharge (Factsheet)

References

1 Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2010, U.S. Geological Survey

2 Managed Aquifer Recharge: An Overview of Issues and Options, Casanova, J, Devau N, and Pettenati M (Book Chapter)

3 History, Santa Clara Valley Water District

4 Imported Water: Vital to Santa Clara County, Santa Clara Valley Water District

5 Groundwater Management Plan, Santa Clara Valley Water District

6 Summary of Managed Aquifer Recharge Concepts and Planning Methods, Gamon D A, Zilles J, and Schumann R (Book Chapter)

7 What We Do, Orange County Water District

8 These numbers come directly from communication with the Water District. Their website also provides storage and usage numbers updated monthly, Orange County Water District

9 What is WIN?, Water Replenishment District of Southern California

10 450,000 acre-ft plus 281,835 acre-ft of adjudicated volume, Water Replenishment District of Southern California

11 Regional Groundwater Monitoring Reports, Water Replenishment District of Southern California

12 FAQs, Kern Water Bank Authority

13 The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), California Department of Water Resources

14 Benefits and Economic Costs of Managed Aquifer Recharge in California, Perrone D and Rhode M M (Journal Article)

15 California Single Family Water Use Efficiency Study, Aquacraft, sponsored by the California Department of Water Resources